Technology, Efficiency, & Inequality: Why Old Politics Aren’t Suited for the New World

The world of the technorati was set ablaze earlier this year by Paul Graham’s blog post on economic inequality. Graham’s piece came at a time of heightened public awareness about inequality. Ever since the Occupy movement of 2011, the problem of “inequality” has been a mainstay in the public discourse — especially as it relates to financial practices. But the recent successes of many darling tech companies has perceptibly shifted the locus of discussion from Wall Street to Silicon Valley.

In early 2015, Apple became the most valuable company in history by reaching a market cap of more than $700 billion. It seemed that Uber was in the news every week last year — but almost always for the same two reasons which, when juxtaposed, draw a stark contrast: investors dumping astronomically large amounts of money into Uber’s bank accounts and users (both customers and drivers) kvetching about the unpredictable and exorbitant fees charged by the service. And the incessant media coverage of “unicorns” last year meant that we seldom went a day without seeing the words “1 billion dollars” and “tech startup” in the same sentence.

Startups, Silicon Valley, and technology as a whole have great potential for creating wealth and adding real value to our economy. Economic activity (in general) does not have to be a zero-sum game, in which some people get rich at the expense of others. When the sewing machine was invented, workers went from producing one dress per day to 10 dresses per day. These technological increases in productivity are real and significant drivers of economic growth. It would simply be unproductive to limit the value-adding potential of technology companies.

But it is important to appreciate the full import of the phase-change in technological capability we are currently experiencing. The progress made by information technologies in recent decades is fundamentally different than anything we’ve seen before.

To illustrate just how much the 21st Century economy differs from the 20th Century economy, consider the following tale of two companies (taken from The Second Machine Age by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee): At its prime in 1997, Kodak was a $30 billion enterprise that employed 145,000 people and indirectly employed thousands more through its complex supply chain and distribution networks. Today, Facebook is a $278 billion company that employs 11,000 people (with no supply chain and a relatively concentrated distribution network). Facebook has created at least 7 billionaires, all of whom have a net worth more than ten times that of Kodak’s founder and wealthiest employee.

Comparing these two companies is particularly poetic, as the rise of smartphones and digital photo-sharing on Facebook has rendered the once-giant Kodak obsolete. Kodak now employs a paltry 6,500 employees, meaning that it took less than 20 years for 140,000 middle-class jobs to simply evaporate.

It is very hard to characterize this story as one of technological progress. Suddenly the sewing machine analogy is not as useful as we thought. Indeed, this example makes it startlingly clear that technology is fundamentally changing our economy and, in particular, the ways in which wealth gets distributed in our society.

How Exactly Does Technology Lead to Inequality?

In the 1930s, the influential economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that we would all be working 15 hours a week, empowered by technological productivity. In the 1960s, a Senate subcommittee heard testimony about the coming crisis of leisure time, brought on by a new economy in which people would only be working 20 hours a week. It’s easy to laugh this off as the mania du jour of bygone eras, but understanding why bona fide experts were so wrong about this is central to understanding our modern economy — and how we should respond to it.

A simplistic explanation for the lack diminishing workloads is that people are greedy. Why only make $50,000 working 20 hours a week when I could make $100,000 working 40 hours a week? This may have something to do with it, but it cannot be the whole story. Indeed, economists were right to predict that technology reduces the amount of menial work that humans do on a regular basis. Any task that requires repetitive, mechanical, or algorithmic work is something that has been automated. But what they didn’t predict is the complexity required to manage and develop all this new technology.

As technology becomes more and more capable, it also becomes more complex. This has two effects. First, it means that the overall level of sophistication required to manage the technology is much higher than before. The person who used to pull the crank at the factory is likely unqualified to engineer a robot and develop the software it takes to do the same job. However, even if all the crank-pullers could acquire modern technical skills, many of them would still be out of a job. It is simply more efficient to have fewer people work more hours rather than having many people work fewer hours.

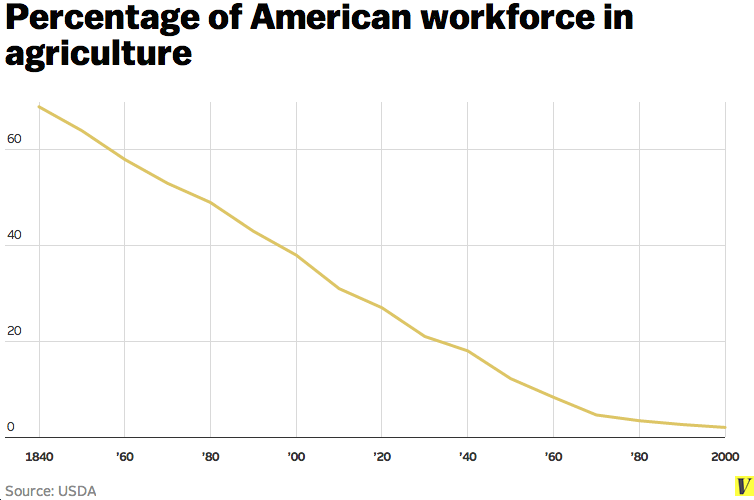

Take farming as a concrete example. Rather than training, equipping, and coordinating the efforts of many farmers all over the country, it just works better to have a few well-trained farmers produce more food. Even though the distributed-labor scenario would mean all farmers would have to work less, it is not economically efficient. And if free market economies are good at anything, it is rewarding efficiency.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for efficiency. But the economic forces described above guarantee that efficient policies increasingly and inevitably lead to more unequal societies. Although it may be unintuitive, average salaries can go up (increased efficiency) while the median salary goes down (increased inequality). As with almost all things quantitative, the devil is in the distribution.

Old Politics Don’t Suit the New World

Unfortunately, the current political climate makes it difficult to integrate the imperatives of efficiency and equality. The libertarianism of Silicon Valley is great at maximizing efficiency, but it offers no solutions to the problem of increasing structural unemployment caused by technological progress. This is why Paul Graham’s appeals to “attack poverty” ring hollow. It is laudable that libertarians emphasize the importance of giving everyone equal opportunity. But as the distribution of wealth becomes more extreme, giving everyone an equal opportunity is like giving everyone a Powerball ticket. Sure, the lottery is a “fair” process, but it does nothing to address the fact it is simply built into the system that the majority of people walk away with nothing.

Liberals and progressives often swing the pendulum too far in the other direction. By emphasizing equality above all else, they often advocate for regressive protectionist policies that fight the inevitable tide of economic progress. Bemoaning the fact that there are fewer middle-class jobs with job security and good benefits ignores the ways in which technology (and globalization) has changed the means of production. Too often left-wing policies aim to reduce efficiency in the name of increasing equality.

The Solution Must Be Political, Not Technological.

While the economic processes driving economic inequality are apolitical, the way we respond to it is necessarily political. I’m not saying I have the answer, but I don’t think it’s too much to ask that we have policies and politicians that aim to maximize the potential of our economy without disenfranchising the lower and middle classes. Any economist will tell you it’s mathematically impossible to maximize two objectives simultaneously. But it is possible to quantify and find the right trade-offs between conflicting goals.

Continuing to talk about policies in shades of red and blue is to ignore the ways in which technology has changed the dynamics of our economy. Sure there are liberal and conservative sides to wealth redistribution, nationalized health care, guaranteed income, minimum wage hikes, corporate tax rates, migrant worker laws, and bank regulations. But our economy has dramatically changed since party lines were drawn and the right balance between efficiency and equality will not be found by voting for a single-party ticket.

I won’t be so glib as to suggest our politics just needs to co-opt Silicon Valley’s ethos, but I do think our politics needs to evolve. Rather than finding a middle ground between two ideological extremes, we should be seeking an oblique political alternative which is based in the realities of our brave, new, technoligically-driven world.

This essay is cross-posted on Medium here.

Alex Miller is a scientist, developer, and former academic. Feel free to connect with him on LinkedIn.